SCHUBERT HEINZ HOLLIGER - Symphony No. 7 "Unfinished" - IDAGIO

←

→

Transkription von Seiteninhalten

Wenn Ihr Browser die Seite nicht korrekt rendert, bitte, lesen Sie den Inhalt der Seite unten

SCHUBERT Kammerorchester Basel

HEINZ HOLLIGER Symphony No. 7 “Unfinished”

Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer

R. Moser: Echoraum zu Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-FeyerFRANZ SCHUBERT 1797–1828

1 Andante h-Moll D 936a 11.22

Andante in B minor

nach den Entwürfen aus dem Spätherbst 1828 in ein fragmentarisches

Klangbild für Orchester gesetzt von Roland Moser (1982)

based on sketches from the late autumn of 1828 turned into

a fragmentary tone painting for orchestra by Roland Moser

Sinfonie Nr. 7 h-Moll D 759 „Unvollendete“ (1822)

Symphony No. 7 in B minor “Unfinished”

2 I. Allegro moderato 15.40

3 II. Andante con moto 11.16

4 „Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer“ 6.43

für 9 Blasinstrumente es-Moll D 79 (1813)

for 9 wind instruments in E-flat minor

Grave con espressione

ROLAND MOSER (*1943)

5 Echoraum zu „Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer“ D79 (2019) 6.41

after “Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer”

Grave

FRANZ SCHUBERT

6 Deutsche Tänze op. posth. D 820 8.56

bearbeitet für Orchester von / arranged for orchestra by

Anton Webern (1931)

2This recording was made as part of the complete recording of Franz Schubert’s symphonies with the Basel Chamber Orchestra

conducted by Heinz Holliger.

Diese Aufnahme entstand im Rahmen der Gesamteinspielung aller Sinfonien von Franz Schubert

mit dem Kammerorchester Basel unter der Leitung von Heinz Holliger.

3KAMMERORCHESTER BASEL

FLÖTE / FLUTE Isabelle Schnöller Hildebrandt, Regula Bernath, Matthias Ebner (6)

Oboe / OBOE Matthias Arter, Francesco Capraro

Klarinette / clarinet Markus Niederhauser, Etele Dosa

Fagott / Bassoon Matthias Bühlmann, Matteo Claudio Severi, Andreas Gerber (4, 5)

Horn / horn Konstantin Timokhine, Mark Gebhart

Trompete/trumpet Simon Lilly, Jan Wollmann

Posaune / trombone Adrian Weber, Marc Sanchez Martí, Daniel Hofer

Violine / violin 1 Baptiste Lopez, Tamás Vásárhelyi, Mirjam Steymans-Brenner,

Valentina Giusti, Matthias Müller, Dmitry Smirnov, Elena Abbati

Violine / violin 2 Daniel Bard, Nina Candik, Kazumi Suzuki Krapf,

Cordelia Fankhauser, Regula Schwaar Niederhauser,

Rita Nakad, Vincent Durand

Viola Mariana Doughty, Katya Polin, Bodo Friedrich, Stefano Mariani,

Carlos Vallés Garcia

Violoncello / cello Christoph Dangel, Georg Dettweiler, Ekachai Maskulrat,

Martin Zeller (1–3), Alma Hernán

KONTRABASS / DOUBLE-BASS Stefan Preyer, Daniel Szomor, Juliane Bruckmann

Pauken / timpani Alexander Wäber

Heinz Holliger Leitung

www.kammerorchesterbasel.ch

4Special thanks to Freundeskreis Kammerorchester Basel and a patron not named by name for the generous support of the album

A coproduction with Deutschlandfunk and with SRF2 Kultur.

Executive producers: Jochen Hubmacher (Deutschlandfunk), Valerio Benz (SRF 2 Kultur), Marcel Falk (Kammerorchester Basel)

Recording: 22 August 2020, Don Bosco, Basel (1), 24 August 2020, Don Bosco, Basel (2, 3), 27–28 August 2020, Don Bosco, Basel (4–6)

Recording producer and editing: Andreas Werner (1) · Sound engineer: Jakob Händel (1)

Recording producer and sound engineer: Andreas Werner (2, 3), Michaela Wiesbeck (4–6)

Total time: 60.38

Artwork: Christine Schweitzer · Cover photos: Florian Kalotay · Booklet photos: Łukasz Rajchert (p. 3), Roland Schmid (p. 15)

P & g 2021 Sony Music Entertainment Switzerland GmbH

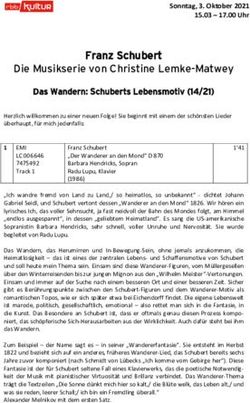

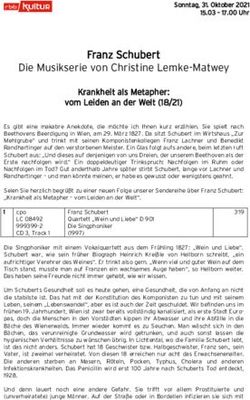

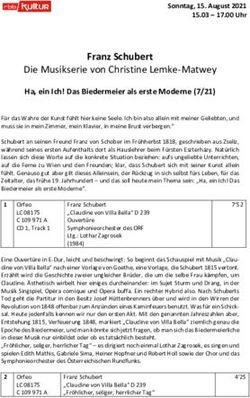

5Schubert-Portrait mit Tod Andante h-Moll D 936a

Die letzte Aufnahme seines Schubert-Zyklus mit dem Kammeror- nach den Entwürfen aus dem Spätherbst 1828 in ein fragmentari-

chester Basel konzipierte Heinz Holliger als ein Schubert-Leben- sches Klangbild für Orchester gesetzt von Roland Moser (1982)

sportrait, das sechzehn Jahre des Komponierens umfasst. In allen Es handelt sich bei diesem Andante um den zweiten Satz einer

Werken ist die Todesnähe präsent. Der Trauermarsch, den Schu- Sinfonie in D-Dur, an der Franz Schubert in den letzten Wochen

bert mit sechzehn Jahren und in der Mitte seines nur knapp 32 seines Lebens arbeitete. Dieser zweite Satz ist im Particell auf zwei

Jahre dauernden Lebens für sein eigenes Begräbnis schrieb, bildet Systemen durchnotiert; der Schluss wurde von Schubert durchge-

den Abschluss; das Andante einer Sinfonie, die er in den letzten strichen. Roland Moser hat dieses Fragment 1982 instrumentiert.

Tagen vor seinem Tod entwirft, den Anfang. Dazwischen steht die Er schreibt dazu: „Dieser Satz in h-Moll gehört zu den ganz gro-

sogenannte „Unvollendete“, die Schubert im Herbst 1822 mit 25 ßen Eingebungen des späten Schubert. Ihn nicht nur Fachleuten

Jahren komponierte, als er erstmals mit den Symptomen seiner zum Lesen zu überlassen, war die Absicht des Bearbeiters. Es wur-

syphilitischen Erkrankung konfrontiert war. „Solche Werke de kein einziger Takt dazu komponiert. Die Orchesterbesetzung

schreibt man nur für sich selbst“, sagt Holliger zu den hier versam- ist die der h-Moll- und C-Dur-Sinfonien: mit zweifachen Holzblä-

melten Schubert-Kompositionen. Ihre Zusammenstellung ist be- sern, Natur-Hörnern, D-Trompeten, drei Posaunen, Pauken und

merkenswert, denn noch nie wurde die „Unvollendete“ in solcher Streichern. Die ‚Löcher‘ im skizzierten Satz wurden aber mit Aus-

Umrahmung auf einem Tonträger gezeigt. nahme einer (später eingefügten) ‚himmlischen‘ Fis-Dur-Episode

Der erste Teil verschmilzt dabei zu einem einzigen Werk, denn nicht aufgefüllt, so dass der Fragment-Charakter spürbar bleibt.

das h-Moll-Andante verbindet sich fast bruchlos mit den beiden Der von Schubert durchgestrichene Schluss wird – gleichsam pri-

Sätzen der „Unvollendeten“: ähnliches Tempo, ternärer Takt und vat – von einem Streichquartett gespielt, nachdem der Dirigent

die äußerst seltene Tonart h-Moll, die Christian Schubart, dessen den Taktstock weggelegt hat. Es wurde also keine Vervollständi-

Gedicht Die Forelle Schubert mit seiner Vertonung weltberühmt gung angestrebt.“

machte, 1784/85 in einer Weise charakterisierte, als hätte er die Roland Moser behandelt Schuberts Entwurf nach den Regeln

„Unvollendete“ vorausgeahnt, denn sie sei „gleichsam der Ton der heutiger Restaurierungskunst, die darin besteht, zum Beispiel bei

Geduld, der stillen Erwartung seines Schicksals, und der Ergebung einem nur teilweise erhaltenen oder beschädigten Fresco, auf kei-

in die göttliche Fügung. Darum ist seine Klage so sanft, ohne je- nen Fall das Original wiederherzustellen, sondern dessen ur-

mahls in beleidigendes Murren, oder Wimmern auszubrechen.“ sprüngliche Gestalt allerhöchstens mit Umrissstrichen anzudeu-

6ten. Die erhaltenen Teile gewinnen dadurch an transzendenter Beginn der Durchführung lässt Schubert es bis an den untersten

Kraft; sie verweisen auf ein Anderes, Unvollendetes, Vergangenes, Klangrand des Orchesters sinken, um es anschließend ‚hochzuheben‘

Zukünftiges. Solche Wirkungen entfaltet gleichfalls das fein inst- und es quasi ans ‚Tageslicht‘ zu bringen. Statt also in der Durch-

rumentierte und die raffinierte Kontrapunktik betonende „frag- führung traditionellerweise das Hauptthema der Exposition zu

mentarische Klangbild“ von Roland Moser. Gerade mit dieser verarbeiten, gestaltet Schubert die gesamte Durchführung ausschließ

Kontrapunktik weist Schubert für Heinz Holliger in eine völlig lich mit diesem magischen Thema. Satztechnisch und harmonisch

neue Welt, die auch schon im schauerlichen Beginn der „Unvoll- schafft Schubert hier eine radikal neue Musik, die bis zu Gustav

endeten“ angelegt ist: „Kurz vor seinem Tod führt Schubert die Mahler vorausgreift; man verliert die Orientierung und gerade bei

Zuhörenden an die geheimnisvolle, nie erklärbare Schwelle, die zu Holligers Interpretation kann einem ob der entfesselten Triebkräfte

überschreiten keinem Lebenden je gegeben ist. Hier ist auch der angst und bange werden. Zwar verschwindet diese unheimliche Welt

Ort des geheimnisvollsten Sinfoniebeginns, der je von einem während der Reprise, aber in der Coda wird sie mit fast magne

Komponisten gefunden worden ist.“ tischer Kraft nochmals angezogen, und der Satz endet in dieser

geisterhaften Stimmung.

Franz Schubert: Sinfonie Nr. 7 h-Moll D 759, „Unvollendete” (1822) Dieses Bedrohliche erscheint im ersten Satz auch in Form einer

Für Heinz Holliger ist die „Unvollendete“ ein vollendetes Werk, Leere, eines tiefen Abgrunds: Mitten im lyrischen Seitensatz reißt

das keiner Ergänzung bedarf. Und so interpretiert er das Werk auch: die unschuldige Musik ab – eine Schrecksekunde, die bei Holliger

die beiden Sätze stehen janusköpfig zueinander und bilden ein zur Grabesstille wird, in die er dann die Fortissimo-Akkorde hinein

Ganzes, – und hinter beiden lässt Holliger die Totenmaske durch- donnern lässt. Der zweite Satz wirkt in seiner Lyrik scheinbar wie eine

klingen. Der erste Satz der „Unvollendeten“ besteht aus einer dop- Idylle; frei und zugleich befreit fügen die Themen sich aneinander.

pelten thematischen Identität. Die eine Identität bildet sich aus der Die Durchführung, die im ersten Satz eine neue Welt ankündet, ist

traditionellen Disposition eines klagenden Hauptthemas und eines im zweiten zu einer kurzen Überleitung regrediert. In seiner Inter-

besonders ‚schubertisch‘ liedhaften Nebenthemas. Die andere pretation zeigt Holliger das Gefährdete dieser Idyllik: Er lässt die

Identität ist untergründig und weniger greifbar; sie erklingt gleich dunklen Töne erklingen, hebt die Einbrüche hervor; so wird das

zu Beginn, beim „geheimnisvollsten Sinfoniebeginn“: ein düster oft wiederholte und schon fast überirdisch schöne Anfangsthema

in die Tiefe absteigendes Thema der Violoncelli und Kontrabässe. der Streicher zu einem Symbol bedrohter Hoffnung. Das von der

Dieses Thema bleibt nicht schattenhaft im Hintergrund, denn zu Klarinette vorgetragene Seitenthema erklingt in gläserner Zer-

7brechlichkeit und strahlt Einsamkeit statt Trost aus. Gerade bei karg Der Trauermarsch ist in der ungewöhnlichen Tonart es-Moll (mit

gesetzten Stellen lässt Holliger die Musik förmlich erstarren, ganz 6 -Vorzeichen) geschrieben, in der sich für Holliger das Kürzel

besonders vor der Coda. Der Kitsch, der bei diesem Satz zuweilen „S“ und damit eine musikalische Unterschrift von „(e)Schubert“

Urstände feiert, wird von Holliger mit stählernem Besen weggewischt, versteckt. Die erste Hälfte des kurzen Werkes besteht aus einem Duo

selbst der erlösende Schlussklang, der meist als auskomponiertes der beiden Naturhörner. Für sie ist die Komposition besonders an-

Lebewohl interpretiert wird, kommt bei ihm wie aus einer anderen spruchsvoll, denn die chromatischen Töne müssen gestopft werden.

Welt und verbleibt in einem eisig kalten Licht. Und Schubert verlangt für seinen Trauermarsch besonders viele

gestopfte Töne. Am auffälligsten ist die Monothematik. Schubert

Schubert: Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer für 9 Blasinstrumente wiederholt die geradezu elend traurige Melodie wie auf der Walze

es-Moll D 79 (1813) einer Drehorgel, und der zweite Teil mit allen neun Instrumenten

Roland Moser: Echoraum zu Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer ist nichts anderes als die ins Tutti gesteigerte Wiederholung des Horn-

D 79 (2019) Duos, allerdings ohne dessen auffällige Triller. In diesem Insistieren

Die Komposition Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer, die Schubert mit auf einer einzigen Melodie hat das Werk schon fast Konzeptcharakter,

sechzehn Jahren schrieb, enthält in Holligers Auffassung bereits und es fordert musikalische Reflexionen geradezu heraus.

den Kern dessen, was später bei der „Unvollendeten“ und der Großen Solch eine Reflexion zu Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer hat Roland

C-Dur-Sinfonie zur Blüte kommen wird. Bereits in der axialsymme Moser für den Schubert-Zyklus des Kammerorchester Basel kom-

trischen Anlage der Melodie, die an ein Kreuz-Motiv erinnert, und poniert: „Meine Reaktion auf diese Komposition nimmt, gleichsam

die sich sowohl im magischen Thema der „Unvollendeten“ als auch in einem ‚Echoraum‘, die Idee der Vergrößerung auf. Wie vor Sonnen

im Thema des h-Moll-Andante wiederholt, sind für ihn die späteren untergang große, lange Schatten auf dem Boden sichtbar werden,

Kompositionen vorbereitet. Wegen dieser inneren Verbindung lässt sind die Motive in stark verlangsamter Bewegung zeitlich gedehnt.

Holliger das rätselhafte Frühwerk dem späten Meisterwerk un Im Wesentlichen läuft das Ganze Takt um Takt nochmals ab, bloß

mittelbar folgen. Er weist damit auch auf die herausragende Rolle mit auskomponierten Wiederholungen. Die ‚Schicksalstonart‘ es-

der Naturhörner hin, denn ihr sanft-klagender Ton erklingt fast Moll bleibt durchwegs spürbar – etwas erweitert, freilich.“

bei allen wichtigen Stellen der „Unvollendeten“, und im Bläser- Moser behält Schuberts Grundbesetzung mit je zwei Klarinet-

stück werden sie zu eigentlichen ‚Türstehern‘ zur musikalischen ten, Fagotten, Hörnern und Posaunen plus ein Kontrafagott bei,

Unterwelt.

8aber erweitert für seinen Echoraum diese Besetzung in subtiler Weise am 7. Mai 1931 im Großen Wiener Musikvereinssaal die Urauf

mit dreizehn weiteren Instrumenten: Pauke, fünf Bratschen, vier führung. Nach dem Konzert bat Emil Hertzka, der Leiter des Wiener

Violoncelli und drei Kontrabässen. Es ist also ein Kammerorchester Musikverlages Universal Edition, nicht etwa einen Schubert-

ohne Diskantinstrumente, – ohne Flöten, Oboen und Violinen. Wie Spezialisten darum, das Werk zu orchestrieren, sondern ausge-

ein Klangalchemist setzt Moser dieses Instrumentarium ein. Es gibt rechnet den Zwölftöner Anton Webern, der dankend annahm. An

kein einziges Tutti im Stück, sondern ständig wechselnde Farben, und seinen früheren Lehrer Arnold Schönberg schrieb er: „Ich war be-

unterschiedliche Funktionen und Rollen der Instrumente. Moser müht, auf dem Boden der klassischen Instrumentationsideen zu

setzt die Instrumentengruppen oft wie Register ein: Die fünf Bratschen bleiben, aber sie in den Dienst unserer Idee von Instrumentation

initialisieren und beenden den Echoraum mit dem es-Moll-Klang, (als Mittel zur möglichsten Klarlegung des Gedankens und Zusam

die vier Violoncelli übernehmen die führende Rolle und evozieren menhangs) zu stellen.“

Schuberts Trauermarsch. Ausgerechnet die Kontrabässe spielen mit Als offizielle Uraufführung von Weberns Schubert-Orchestrierung

Flageoletts oft in der Diskantlage, und die Klarinetten ziehen weite gilt das Funkkonzert der Volksbühne Berlin vom 25. Oktober 1931

Kantilenen, die auf die magischen Klarinettenstellen im zweiten Satz unter der Leitung von Hermann Scherchen. Schon drei Tage früher

der Unvollendeten verweisen. Mosers Echoraum dauert fast genauso allerdings führte Ernest Ansermet das Werk in Genf auf. Und am

lang wie Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer. Trotz des Variierens und 29. Dezember 1932 konnte es Anton Webern mit dem Frankfurter

der Sparsamkeit der Mittel, die in ihrer Präzision an Anton Webern Rundfunk-Orchester selbst dirigieren, – einen Monat vor der Macht

erinnern, erschafft Moser eine sich weitende und befreiende Musik, übernahme der Nationalsozialisten. Die Aufnahme ist ein äußerst

die sich wie ein ‚Segen‘ über Schuberts Begräbnismarsch legt. wertvolles Dokument. Webern geht mit den Tempi sehr frei um,

differenziert sie mikro-agogisch und mikro-dynamisch. Seine Or-

Schubert: 6 Deutsche Tänze, op. posth. D 820 chestration leuchtet wie mit einem Scheinwerfer, exquisite Stellen

bearbeitet fürs Orchester von Anton Webern (1931) Schuberts aus. An Alban Berg schrieb Webern treffenderweise: „Es

Über hundert Jahre nach seinem Tod wurden 1931 im Archiv der sieht aus wie eine klassische Partitur und doch wieder wie eine von

Wiener Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde Schuberts Deutsche Tänze mir.“ Holliger übernimmt Weberns Ansatz feinster Rubati und inter

entdeckt. Der Pianist Otto Schulhof, berühmter Begleiter zum Bei pretiert Schubert aus dem Geiste der Moderne heraus.

spiel von Pablo Casals, Jascha Heifetz oder Lotte Lehmann, spielte

g Roman Brotbeck, 2021

9A Portrait of Schubert with the Figure of Death Schubert later set Schubart’s poem Die Forelle (The Trout), ensuring

Heinz Holliger has conceived the final release of his Schubert cycle the poem’s immortality.

with the Basel Chamber Orchestra as a portrait of the composer’s

life spanning the sixteen years of his compositional activities. Each Andante in B minor, D 936a

work is marked by the presence of Death. The funeral march that based on sketches from the late autumn of 1828 and turned into a

Schubert wrote for his own burial when he was sixteen – just halfway fragmentary tone painting for orchestra by Roland Moser (1982)

through a life that lasted less than thirty-two years – brings this The present Andante is the second movement of a symphony in

recording to an end. It begins with an Andante from a symphony D major on which Schubert was working in the final weeks of his

that he drafted only days before his death. Between them comes life. In the surviving short score this movement is notated on two

the “Unfinished” Symphony that he wrote in the autumn of 1822, staves. The ending was struck out by Schubert. Roland Moser in-

when he was twenty-five and was first confronted by the symptoms strumented this fragment in 1982, when he noted that “This move-

of the syphilis that was to kill him. “One writes such works only for ment in B minor is one of the late Schubert’s most inspired. It was

oneself,” says Holliger about all the pieces featured here. Their the aim of the present arranger to ensure that not just experts can

juxtaposition is remarkable in that the “Unfinished” Symphony has read it. Not a single bar has been added. The orchestral resources

never previously appeared on a recording within such a framework. are identical to those of the B minor and C major symphonies:

The first two pieces blend together to create a single work inasmuch double woodwind, natural horns, trumpets in D, three trombones,

as the B minor Andante merges almost seamlessly with the two timpani and strings. The ‘gaps’ in the sketch have not been filled in,

movements of the “Unfinished” Symphony. We have the same tempo, the only exception being the ‘heavenly’ episode in F sharp major

the same triple metre and the same unusual key of B minor, which that was inserted later. In this way the movement’s fragmentary

Christian Schubart characterized in 1784/85 in a way that reads character remains intact. The final section was struck out by Schubert

almost like a premonition of the “Unfinished” Symphony. It was, he but is performed here by a string quartet after the conductor has

wrote, “the key of patience, so to speak, the key of someone calmly put down his baton, resulting in a quasi-private performance. In

awaiting his fate and submitting to divine providence. That is why short, no attempt was made to complete the movement.”

there is such a gentle note of lament that never spills over into offen Roland Moser’s approach to Schubert’s draft may be compared to

sive grumbling or whining.” It may be mentioned in passing that that of a modern art restorer whose task consists in no more than

10indicating the outlines of a fresco that has survived only in part or from the traditional design of a plaintive first subject and a song-

in a damaged condition. His or her aim is not to reconstruct the like second subject that is typically Schubertian in character. The

original. As a result of this restoration work the surviving parts gain second identity is more cryptic and less tangible: it is heard right at

in transcendental power and point to something different, some- the beginning, with its “most mysterious opening of a symphony

thing incomplete that belongs to both the past and the future. This that a composer has ever devised”. Here a theme in the violoncellos

is the effect achieved by Moser’s “fragmentary tone painting”, and double basses descends into the sepulchral gloom, but, far

which stresses the subtly instrumented and sophisticated counter- from leading a shadowy existence in the background, it sinks down

point of Schubert’s sketch. And it is very much this counterpoint to the orchestra’s lowest extreme at the start of the development

which, in Heinz Holliger’s view, finds Schubert entering an entirely section only then to be lifted up and, as it were, brought into the

new world, a world already adumbrated in the eerie opening of the light. In other words, Schubert does not rework the main theme from

“Unfinished” Symphony: “Shortly before his death Schubert led the exposition, as is traditionally the case in a development section,

his listeners towards a mysterious and inexplicable threshold that but instead he uses the magical second subject as the material for

no living soul is permitted to cross. This is the point at which the the whole of this section. In terms of both compositional tech-

symphony begins, the most mysterious opening of a symphony nique and harmony Schubert has created a radically new kind of

that a composer has ever devised.” music that looks forward to Mahler. We lose our bearings and –

especially when we hear Heinz Holliger unleashing the movement’s

Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 7 in B minor, D 759, driving forces – we may well feel anxious and afraid. Although this

“Unfinished” unsettling world vanishes during the recapitulation, it returns in

For Heinz Holliger the “Unfinished” is a finished work, one that the coda as if drawn by a magnetic force, and the movement ends

requires nothing to make it more perfect. And this is also how he on this note of unearthly ghostliness. This sense of threat also finds

performs the piece: the two movements are related to one another expression in the symphony’s opening movement in the form of

like the two faces of Janus that together form a whole – and behind emptiness and the feeling that we are staring into an abyss: in the

both faces Holliger detects a death mask that he allows us to hear middle of the lyrical second subject this innocent music abruptly

in his interpretation. The symphony’s opening movement is notable breaks off, a moment of terror that in Holliger’s hands resembles

for its twofold thematic identity: the first of these identities stems the silence of the grave broken by the following fortissimo chords.

11The second movement has a lyricism to it that seems idyllic: its fully fashioned in the “Unfinished” and the “Great” C major Sym-

themes fit together with a freedom that is also liberating. The develop phonies. These later works are already adumbrated in the axial

ment section, which in the opening movement had heralded a new symmetry of a melody that recalls a cruciform motif and that is

world, is here reduced to the status of a brief transition. In his own repeated both in the magical theme of the “Unfinished” Symphony

interpretation of this movement, Holliger shows us how threatened and in the theme of the B minor Andante. It is this internal con-

this idyll is: he stresses the dark tones and focuses on the fissures nection that has persuaded Holliger to perform the mysterious

in the landscape. In this way, the oft-repeated opening theme in the early work immediately after the late masterpiece. The conductor

strings, with its almost otherworldly beauty, becomes a symbol of also draws attention to the prominent roles of the natural horns,

imperilled hope. The second subject in the solo clarinet has a glassy whose quietly plaintive tone is heard at almost every important

fragility to it that radiates loneliness rather than consolation. In aus- juncture in the “Unfinished”. In this piece for wind instruments,

terely scored passages, in particular Holliger allows the music to os- they stand guard outside the gates to the musical underworld.

sify, more especially just before the coda. All too often this move- The funeral march is in the unusual key of E flat minor (with six flats).

ment is a breeding ground for kitsch, but such a reading is swept In German nomenclature this key is called es-Moll. Holliger believes

away by Holliger as if with a wire brush, and even the final sound, that Schubert chose it as a coded reference to his own musical

which brings a note of redemption and is generally interpreted as signature of “(e)Schubert”. The first half of this short work consists in

the musical expression of a fond farewell, appears to emerge from a duet for the two horns. The writing for these instruments is especially

another world, remaining exposed in a light that is as cold as ice. challenging as the chromatic notes have to be produced by stopping

them, and Schubert demands an abnormally large number of stopped

Schubert: Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer notes in his funeral march. But perhaps the piece’s most striking

for 9 wind instruments in E-flat minor, D 79 (1813) feature is its monothematicism. The pitifully sad melody is repeated

Roland Moser: Echoraum after Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer, as if on the cylinder of a barrel organ, while the second half, which

D 79 (2019) calls on the resources of all nine instruments, is simply a tutti repeat

In Holliger’s view, Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer (Franz Schubert’s of the horn duet, albeit lacking the duet’s striking trills. This insistence

Burial Ceremony) that Schubert wrote when he was sixteen already on a single melody invests the work with an almost conceptual

contains within it an embryonic version of what was later to emerge character and positively demands a musical response to it.

12One such response to Franz Schuberts Begräbniß-Feyer is Roland in the second movement of the “Unfinished”. Moser’s Echoraum

Moser’s contribution to the Schubert cycle of the Basel Chamber lasts almost exactly as long as Franz Schuberts Begräbniß- Feyer.

Orchestra: “My reaction to this composition takes up the idea of Despite the variety and economy of resources whose precision re-

magnification as if in an echo chamber. Just as long shadows be- calls the music of Anton Webern, Moser has created an expansive,

come visible on the ground before sunset, so the motifs are liberating piece that lies like a blessing upon Schubert’s funeral march.

stretched out in time with the result that they move much more

slowly. In essence the whole work unfolds once again, bar by bar, Schubert: 6 Deutsche Tänze, op. posth. D 820

but with the repeats written out in full. The key of E flat minor that arranged for orchestra by Anton Webern (1931)

is associated with fate remains discernible throughout the piece, In 1931 – over a century after Schubert’s death – the composer’s

albeit somewhat expanded, of course.” Deutsche Tänze were discovered in the archives of the Gesellschaft

Moser retains Schubert’s original resources of pairs of clarinets, der Musikfreunde in Vienna. Scored for piano solo, they received

bassoons, horns and trombones together with a single contrabas- their first performance in the Great Hall of the Musikvereinssaal

soon but he expands these forces in the subtlest of ways by adding on 7 May 1931. The soloist was Otto Schulhof, the famous accom-

a further thirteen instruments: timpani, five violas, four violoncel- panist of several major artists, including Pablo Casals, Jascha Heifetz

los and three double basses, resulting in a chamber orchestra with and Lotte Lehmann. Following the performance the head of Uni-

no treble instruments – there are no flutes, oboes or violins. Moser versal Edition, Emil Hertzka, decided to commission an orchestral

deploys these instruments in the manner of a musical alchemist. version of them but instead of approaching a Schubert specialist, he

There are no tutti passages in the piece, only constantly changing turned to Webern, who was more famous as a serial composer and

colours, while the instruments perform different functions and who gratefully accepted the commission, writing to his former teacher,

play a variety of different roles. The instrumental groups are often Arnold Schoenberg, “I was at pains to remain in the realm of classi-

used like organ stops: the five violas initialize and end Echoraum cal ideas on instrumentation, while placing those ideas in the service

with the sound of E flat minor, while the four violoncellos assume of our own idea on instrumentation – as a means of elucidating the

the leading role and conjure up Schubert’s funeral march. The thought and its context in the clearest way possible.”

double basses often play harmonics in their treble register, and the The official premiere of Webern’s orchestration of Schubert’s

clarinets paint other lines that recall the magical clarinet passages German dances is usually regarded as a radio concert conducted

13by Hermann Scherchen at the Berlin Volksbühne on 25 October

1931, although Ernest Ansermet had in fact conducted the work three

days earlier in Geneva. Webern himself conducted a performance

with the Frankfurt Radio Orchestra on 29 December 1932 – just a

month before the National Socialists came to power in Germany. The

recording that was made on this occasion is an extremely valuable

document: Webern adopts a very free attitude to the tempi, intro

ducing micro-agogic and micro-dynamic subtleties, while his

orchestration serves to highlight the exquisite writing of the original.

Webern’s comment in a letter to Alban Berg is apposite in the ex-

treme: “It looks like a classical score but also like one of mine.”

Heinz Holliger follows Webern’s lead, introducing the subtlest

rubatos and interpreting Schubert in the spirit of musical modernism.

g Roman Brotbeck, 2021

Translation: texthouse

14G010004433129C

Sie können auch lesen